Oscar Nominations:

Documentary Feature

A few weeks ago I wrote a review of Julian Schnabel’s At Eternity’s Gate, a movie that earned Willem Dafoe a best actor Oscar nomination for his portrayal of Vincent Van Gogh. In that review I argued that Schnabel – himself a contemporary painter before moving into film – had created a movie that used the elements of the film-makers craft much in the same way that Van Gogh used the elements of painting. Schnabel made elaborate use of thickly-applied cinematography techniques, like colored, even blurry lenses and lush landscape colors to tell his story, exactly like Van Gogh paints with layer upon layer of paint. The result is a movie that conveys van Gogh’s expressionism not just in the story told, but in the technique used to tell it. It was an interesting and revealing use of film-making techniques to tell a biographical story.

What might happen, if a film-maker chose to make a film mirroring some other movement in painting? What, for example, would a movie look like if it were framed in, say, a cubist mode, using, as in the style of Picasso, instead of van Gogh’s? What would a movie look like that abandoned the sense of a storyline and, instead, tried to paint a portrait by using fragments of time and instances of perspective, much like Picasso would break apart a subject into composite views all taken through different filters? Can a movie convey a message, a feeling, an understanding without telling a conventional story?

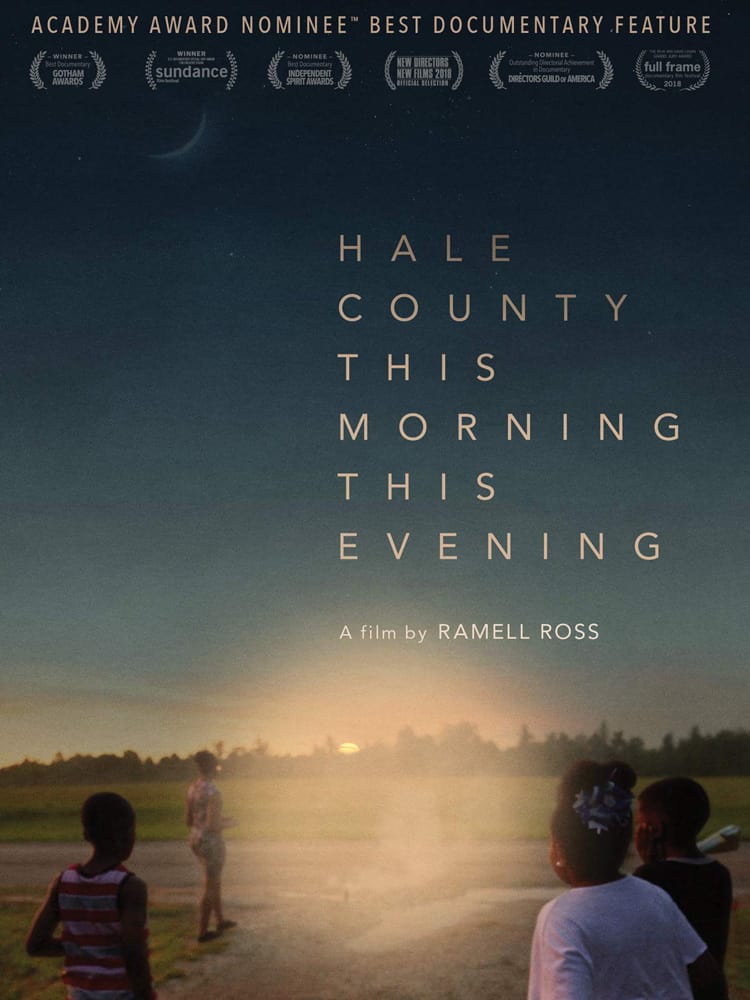

I think Hale County This Morning, This Evening is such a movie. How well it succeeds is clearly an interesting question and I am certain the range of opinions about this movie will be broad. Although critics rated this movie in the top third of the Oscar-nominated movies, audiences placed it at the very bottom, as in the worst of all 37 movies. So clearly, this is an ‘artsy’ film that is not going to please everyone. In my small movie group, there was a general consensus that this movie wasn’t very good. Andy even thought it wasn’t even worth a review, that it did nothing to provide a story line that would stimulate empathy for the characters. My wife Joan called it ‘disjointed’ and ‘fragmented’ and, in the end, sort of ‘pointless’.

They aren’t wrong – the movie is all of that. I had the impression while watching it, that what we were watching was similar to walking through an art gallery and viewing paintings randomly, without benefit of a curator or theme. But, at the same time, many of the images were of stunning quality and the movie demands that you pay attention to what you are seeing. Odie Henderson, a RogerEbert.com critic noted that “It’s immersive lyricism demands the full brunt of our attention.” Luke Moody of Sight & Sound writes “Sometimes you can see the world differently just by sitting still and taking the time to look at it.’” Mary Ann Johanson, the FlickFilosopher, writes “Slice of life and stream-of-consciousness, this is unlike any documentary before about what it’s like to be poor and black in America…Ross (the director/writer/cinematographer/ editor) approaches his subjects more in the spirit of poetry and Impressionism than journalism or sociology.” And “There’s plenty that’s straight-up beautiful here, but Ross also finds beauty in everyday mundanity, like a toddler’s joy at the newfound skill of running.”

RaMell Ross, who created this movie, is a black man who started by playing basketball at Georgetown University. From there he went to the Rhode Island School of Design and then taught film at Brown University in Providence. In 2009 he moved to Hale County, Alabama, an area saturated with the Alabama traditions of black-soil cotton history, where he spent the next decade living with the black Americans that became the focus of this movie. He spent five years filming them, collecting more than 3600 hours of motion picture film. For this movie, he edited that huge volume down to just 76 minutes, capturing what he believed was the essence of his experience and his subjects lives.

Like a cubist painting, his images do not tell a linear story, but rather they intentionally fragment his subject into disparate experiences each of which communicate a single impression or feeling. Like a cubist painting, the individual frames do not merge into a coherent whole. And yet, somehow, if we let the stream of consciousness flow over us, like the multiple perspectives of a Picasso painting, we do construct an appreciation and even an empathy for the beauty of the whole.

If a viewer wants to appreciate Hale County, then they must significantly alter their normal, movie-going frame of mind. The viewer isn’t being told a story – he is being given clues and hints that have to be combined inside the viewers mind. This is a new kind of movie experience that won’t work for everyone. But for those who allow it, it can be very rewarding. I give it four stars.