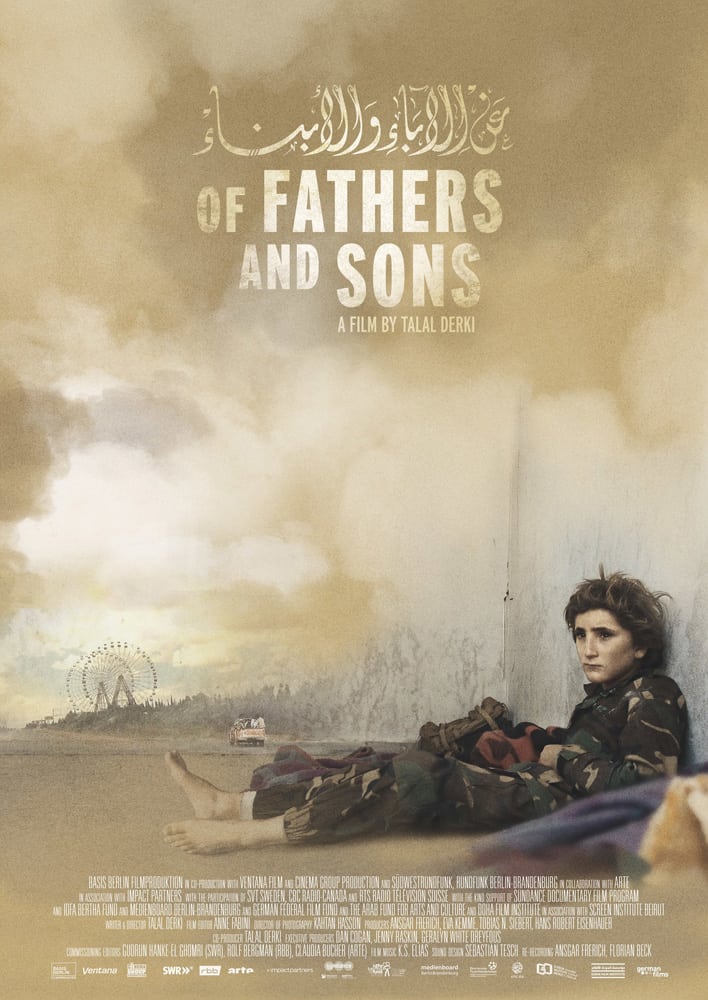

Oscar Nominations:

Documentary Feature

Our fourth documentary feature of the year, Of Fathers and Sons shares with the last two (Minding the Gap and Hale County…) the ‘immersive’ qualities of the filmmaker spending considerable amounts of time with his subjects. In Hale County and Minding the Gap, the film makers spend a decade or more living with their characters and, ultimately, becoming as much a part of the story as the people on the other end of the camera.

In Of Fathers and Sons our filmmaker, Talal Derki, scores a major film-making coup by spending two years in a small town in Idlib province Syria, living with the Osama family. Past documentaries have communicated the horror of the Syrian situation in documentaries like The Last Men in Aleppo or The White Hats. So we’ve seen this kind of story before.

What makes Of Fathers and Sons different is that Derki has managed to embed into the family of a radical jihadist – in fact a member of Al Qaeda. Born and raised in Syria, Derki received formal schooling in Athens for film making and then relocated his family to Berlin, Germany. A number of organizations in Germany, the US, and several mid-eastern countries helped in the production of this film.

For two years he follows this family and films at least part of their lives in an effort to tell the story from the perspective of ‘the enemy’. Although we sometimes hear the voices of female family members, the camera only portrays the boys and men in this family story. As we follow the Father, the jihadist Abu Osama, as he dismantles land mines and in one, very uncomfortable scene, shoots at someone on a bicycle. We also see his sons (he has six of them, named after Al Qaeda heroes) learning more and more about how to become more like their Father.

The feeling that he leaves us with is not a good one. Osama comes across as a doting father and, despite the poverty of a country torn apart by war, his family seems to live a moderately decent existence. He might be seen as strict with his sons but only in one scene was he bordering on abusive. Still, though, there is something horribly unnerving about seeing how his opposition to western and especially American culture is being radicalized in his sons. By the end of the movie, the fact that one of them has become a full on Al Qaeda terrorist is not at all surprising. At one point Abu Osama says “this is a war of attrition, but it will not go on forever.” Agreeing with Brian Tallerico of rogerebert.com, we don’t really believe him.

But that might be both the beginning and the end of this movie. It is remarkable because of the perspective it provides – within the family of a terrorist. And, like most family traditions, it shows how they are passed down to the next generation. But that’s where the message ends, I think. It does not help us understand where this all came from – how this family got to this position to begin with. Alas, maybe the point of the movie is that causation just doesn’t matter anymore.

The movie gets credit for the risks that the filmmaker took by embedding with this family. But, unlike Minding the Gap, or Hale County, I don’t think this one gives us as much insight into what makes these people tick – their motivations and feelings. As Ben Kenigsberg (of the New York Times) wrote: “If Derki’s goal was to capture what causes ideology to spread, he and his camera look without seeing.” For these reasons, I give it 2.5 stars.